The Irish model: How low should taxes go?

- Published

As the UK government hints it could slash tax rates for foreign businesses after Brexit, Paul Moss looks at how the low corporate tax model is working in neighbouring Ireland.

There is something rather cult-like about the Facebook office in Dublin.

Everyone smiles, everyone seems genuinely delighted to be working for one of the biggest tech firms in the world.

Then there are the primary colours everywhere, the games provided for staff to play, from chess to ping-pong.

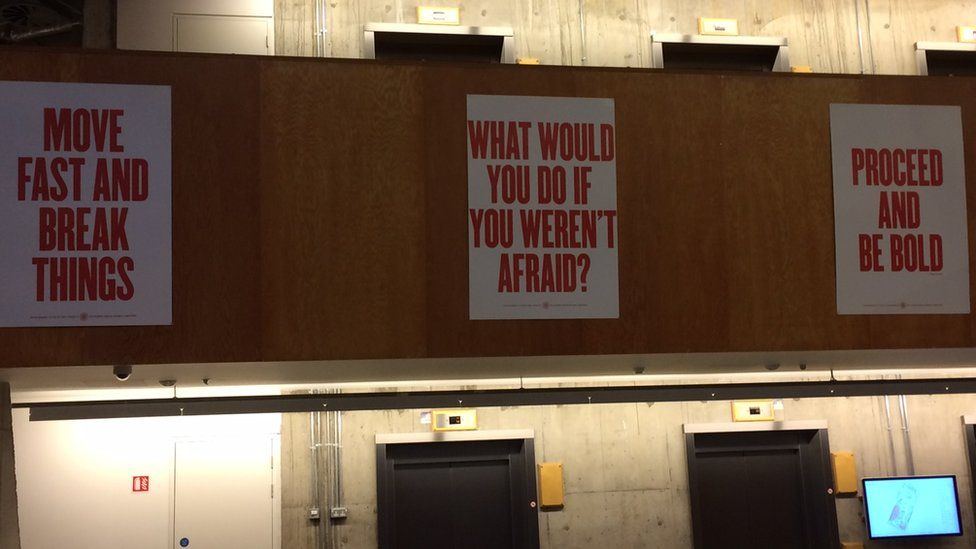

But what most catches your eye are the posters, exhorting staff to improve their performance with slogans like "Proceed and Be Bold," and even "Move Fast and Break Things".

I resisted the temptation to kick over one of the vases in reception, or perhaps hurl a fire extinguisher through the window.

Instead, I proceeded, as planned, to interview the man who runs this office, about why Facebook had chosen Ireland for its international headquarters.

I wanted to ask about the importance of one specific attraction: that companies in Ireland do not have to pay much in the way of tax.

"It is a significant part of our reason for coming here," Gareth Lambe acknowledges.

He is dressed casually, as you might expect of the boss in charge of a major tech company - jeans, v-neck jumper, not a suit or tie in sight.

"The 12.5% corporation tax, which is lower than a lot of other jurisdictions... we've had that for a long time now. It's been very helpful having that kind of certainty here."

'Knock-on benefits'

Mr Lambe is at pains to emphasise that low tax was certainly not Ireland's only appeal.

This is an English-speaking country, with a highly educated workforce, and low costs.

And he also wants me to know how much Facebook contributes to Ireland aside from tax, the 1,600 jobs, and the knock-on wealth these in turn create. "Restaurants, rents paid, cinemas... these multinationals in Ireland actually generate a hell of a lot of economic activity."

And yet, most of these same multinationals were remarkably unwilling to talk to me about their presence in Ireland.

Getting businesses to talk is not usually such a problem, but when I said I wanted to mention the subject of tax, various organisations which represent the commercial world here said it might be impossible to find any companies which would be interviewed.

In the event, Facebook was the only one which came forward.

Part of the problem, I was told, is the sticky topic of tax avoidance.

Companies stand accused of banking their profits in Ireland, where the tax rate is low, even though their operations are really based elsewhere.

Yet the economist Tom Healy believes there may be another reason why CEOs seem to have developed a new-found shyness when it comes to the subject of Ireland's tax rate.

The fact is, as he puts it: "The party is over."

Mr Healy is director of the left-leaning Nevin Institute for Economic Research, and his argument is a simple one: that Ireland had a competitive advantage when it was the only developed nation cutting corporation tax so low, allowing it to lure companies away from other countries.

Now, however, many of those other countries have decided to play the same game.

"A number of East European countries, one or two of the Baltic states, have gone down the road of aggressive tax cuts. And you've really reached the point where it's impossible for a developed economy like Ireland to compete with that sort of policy."

However, East European countries are not though the only ones engaged in this corporate tax-cutting competition.

The United Kingdom under its current Conservative government has already lowered the rate from 28% to 20%, and it is set to drop further, to 17% by 2020.

But more than that, the Prime Minister Theresa May and her Chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Hammond, have dropped heavy hints that further cuts could be on the way.

Indeed, this has been an implicit threat to other European Union states: that if they do not offer Britain an agreeable deal on trade, post-Brexit, Britain might use corporate tax cuts to draw business away from the EU, turning the UK into what one commentator described as "Singapore on the Thames".

"Don't do it," says Tom Healy, with a certainty that belies his otherwise cautious manner.

His fear is that the UK will become part of an international race to the bottom on corporate tax, with countries eventually demanding so little from business that they will no longer be able to fund public services.

"Tax is a factor, but the best way to bring in investment," he believes, "is to develop infrastructure, skills and innovation."

The UK Treasury insists that its corporate tax-cutting approach has so far worked, encouraging investment and enterprise, and thus creating jobs.

Questioned about this recently, Mr Hammond said "By being globally competitive, that's how we protect the living standards and the jobs of our people."

On a freezing cold and windy evening I put these arguments to a Dublin city councillor as we walked through the ward he represents in Coolock, one of the poorer neighbourhoods in Dublin's northern suburbs.

Michael O'Brien points out a local hospital, which he says is suffering from a shortage of beds and staff.

And he tells me about the housing issues he has to deal with, the families in temporary accommodation, and the people sleeping rough.

He refuses to buy the idea that a lower corporate tax rate is an overall benefit to the economy.

"If more tax was demanded of the multinationals and domestic businesses, it would bring in billions of extra revenue that could be spent to deal with the housing crisis, deal with the healthcare crisis," he argues.

"It's insufferable to hear the likes of Facebook extolling this low tax regime. I think people see a basic issue of tax justice."

And with that, Councillor O'Brien heads off to try and deal with a few more problems among his constituents.

And I use my smartphone to order a taxi, check emails and what my friends are posting on Facebook, and soon leave Coolock far behind.

- Published25 January 2017

- Published22 January 2017

- Published14 March 2016