How Progestin, a Synthetic Female Hormone, Could Affect the Brain

Used widely in contraceptions and in hormone replacement therapy during menopause, progestins affect a lot more than just the uterus.

Used widely in contraceptions and in hormone replacement therapy during menopause, progestins affect a lot more than just the uterus.

Progestins are a synthetic version of the naturally-occurring female reproductive hormone progesterone. The compounds were initially designed to counteract certain unwanted effects of estrogen in reproductive tissues, particularly in the uterus. Several generations of progestins have been developed both for use in contraception and in hormone replacement therapy during menopause, and they continue to evolve.

While the target of progestins used in hormone therapy is generally the uterus, progestin therapy affects every major organ system including the brain, the cardiovascular system, the immune system and the generation of blood cells. As in other systems, progestins have unique effects on the brain which ultimately could impact the long-term neurological health of users. Most of the effects of progestins on the brain are beneficial, although some research has shown that they may pose some risks.

- Waiting Longer to Begin HRT May Reduce Your Risk of Breast Cancer

- Oral Contraceptive Use and Bone Mineral Density

- Coping with Menopause

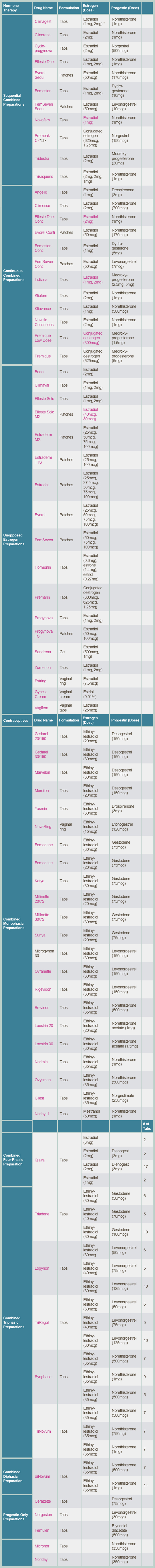

When used as contraceptives, progestins work by preventing ovulation and pregnancy and a table at the end of this article lists the brands currently on the market. They are often combined with estrogen to attain better control of the menstrual cycle -- and to inhibit the maturation of the (young egg cell) more effectively -- as well as discourage ovulation. The majority of contraceptive drugs currently on the market contain estrogen and progestin in combination. Other formulations of hormones, including administration by injection, implants, vaginal rings, transdermal gels, and sprays have also been used for contraception. One of the most common uses of hormone therapy is, of course, to treat menopausal and perimenopausal symptoms that develop from the natural decline of the female reproductive hormones.

Studies are discovering much about the effects of progestins on the brain: Among their benefits, progestins can boost brain regeneration and metabolism, alone or in combination with estrogen. Findings from preclinical studies show that how and when progestins are used, both in contraception and in menopause, can dramatically impact neurological health and cognitive function. Still, some drawbacks have been linked to the use of progestins. The focus of this article is to discuss how progestins work on the brain, including their effects on brain regeneration and metabolism, as well as their effects on cognition.

THE TARGET OF PROGESTINS: THE BRAIN

Though it might seem logical that the sex organs would be the primary target for progestins, in reality, their influence is largely on the brain. This is true both for their use in contraception and for the symptoms of menopause. Progestins interact with a variety of receptors, including estrogen, androgen, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptors. These receptors are abundant in the areas of the brain involved in reproductive function (like the hypothalamus) as well as other brain regions not directly involved in reproduction. These molecules regulate aspects of brain function from how brains cells connect to each other to the birth of new neurons to mood and cognition.

Synthetic progestins were originally developed to overcome the short half-life of progesterone and its high production cost. Progestins are derived from either progesterone or testosterone and there have been many "generations" of progestins that have evolved considerably over the years. The newer generations are generally more active and have less interaction with other types of receptors, which are both advantages.

The interaction between progestins and these receptors is a major source of the unwanted side effects seen in hormonal contraception and hormone replacement therapy, such as the increased risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease. Still, long-term studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the newer generations of progestins, both in contraception and hormone replacement therapy, and to determine their long-term impact on women's health.

Interestingly, progesterone receptors are expressed throughout the brain and can be found in every type of brain cell, which is largely why progestin has many reproductive and non-reproductive effects in the central nervous system. The fact that these receptors are found well beyond the borders of the hypothalamus, which regulates reproductive function, sets the stage for progesterone's many effects on the brain and cognition.

BOOSTING BRAIN CELL REGENERATION

Progesterone is well known to enhance cell growth, and this effect was first noted in the breast and uterus, though it seems to pertain to the brain as well. In the adult brain, the growth of new neurons can occur in two zones. And, as in the uterus, progesterone's regulation of cell division in the nervous system is complex.

Progesterone regulates neural cell proliferation in both the peripheral and central nervous system, and seems to work in a number of ways. It can increase the expression of the genes that enhance cell division and inhibit the ones that repress it. Animal studies have shown that progesterone can increase the growth of progenitor cells in the brain, which are akin to stem cells in other parts of the body. But the effect of progesterone does not seem to continue indefinitely or lead to uncontrolled growth.

When estrogen is combined with progestin, however, as is often the case in hormone therapies, the effect may change. Estrogen alone is neurogenic (that is, it boosts neuron growth), as is progesterone. But when progesterone was administered simultaneously with estrogen, it appears to counteract the neurogenic effect of estrogen.

Progesterone may have some important benefits in the aging brain. There is a natural decrease in the growth of new cells as one ages: Progesterone seems to promote brain cell growth, at least in adult rats, and some studies have shown that it can improve cognitive performance in the aging mouse. This is likely promising news for the aging brain of humans as well. Newer studies continue to suggest ways in which progestin can be used to enhance brain health, while avoiding the risk for tumors that often come with estrogen.

The Evidence for Cell Regeneration

Certain synthetic progestins have been linked to increased DNA synthesis and cell growth both in the petri dish and in live animals. Since estrogen is often paired with progestin, many studies have compared the effect of the hormones singly and in combination. Both hormones can boost neural proliferation by themselves and in combination. Still, much is unknown about the effects of progestin alone, both good and bad. Progestin by itself seems to have a range of effects on the growth and protection of neurons and the natural death of brain cells, which are continuing to be mapped out by researchers.

Helping the Brain's Helper Cells

Another arena in which progestin exerts its effects is in the areas of the brain that give rise to "helper" cells called oligodendrocytes, which are part of the brain's support network. These cells are capable of migrating into places where nerve cells' insulation has been lost to disease or injury, and repairing these sites. Progesterone can enhance the growth of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. The death of oligodendrocytes is one of the features of Alzheimer's disease. While progesterone has been shown to repair the damage to nerve cell insulation, its full potential in Alzheimer's disease treatment needs further investigation, but appears promising.

REGULATING BRAIN METABOLISM

There's some nice evidence that progesterone may promote brain metabolism, working through a number of avenues. Both estrogen and progesterone have the ability to boost the function of mitochondria, the brain's primary energy producers. The two hormones also appear to reduce the "leakage" of free radicals, dangerous little compounds that can damage DNA.

Free radicals cause oxidative damage that has been thought to play a major role in aging and may underlie the cognitive declines associated with it. Estrogen and progesterone both reduce oxidative stress in the brain, which could significantly contribute to brain health.

The impact of progestins on the brain's metabolism has long-term implications for the neurological health of both pre- and postmenopausal women. However, some evidence has shown that progesterone and estrogen have different, sometimes antagonistic, effects when given together. Progestin may counteract certain beneficial effects of estrogen, and the effects of certain types of progestin can differ even from the effects of progesterone on brain metabolism. For all of these reasons, more work will be needed to fully understand the positive and negative effects of each of these hormones on brain metabolism.

PROGESTINS CAN AFFECT COGNITION

In contrast to the abundance of studies on the effect of estrogen and progestin therapy on cognition, the exact effects of progestins by themselves remain elusive. The Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), the largest randomized, controlled study of the kind, found that a group of women treated with conjugated equine estrogen and metroxyprogesterone (one form of progestin) had higher risk of probable, all-cause dementia compared to women who took only estrogen or placebo.

On the other hand, estrogen has been shown to have multiple beneficial effects on brain metabolism and cognition: It seems to be capable of increasing connections among neurons, as well as boost brain metabolism and prevent metabolic decline, especially in regions of the brain most susceptible to Alzheimer's disease. The discrepancies between these studies and findings from WHIMS led to the suggestion that progestins may affect aspects of cognition negatively, diminishing or opposing the beneficial effects of estrogen.

Several important issues, however, were not addressed in the WHIMS study and should be considered to better understand the true impact of progestins on cognition. One of the issues is the type of progestin used in the WHIMS: medroxyprogesterone has been thought to have negative effects on the brain (including memory impairment), as well as antagonize the benefits of estrogen, and even be linked to breast cancer in hormone therapy users.

Because of its widespread use, medroxyprogesterone has been the most extensively studied version of progestin, but much less is known about the variety of progestins used in the hormone therapy and contraceptive preparations. Indeed, other types of progestins seem to have positive effects on cognition. For example, post-menopausal women who took estrogen and micronized progesterone (another form of progestin) for 12 weeks performed significantly better on a working memory task than the estrogen and medroxyprogesterone and the estrogen and placebo groups.

Similarly, rats treated with progesterone, alone or along with estrogen, had improved cognition. Importantly, women who used contraceptive drugs with new generation progestin performed better on mental rotation (a task in which subjects are presented with two objects, often each rotated a specific amount of degrees, and must decide whether the two objects are identical or mirror images) and verbal fluency than women using contraceptive drugs with older generation progestins.

The timing of how progestins are administered (continuously or cyclically) also influences how they affect cognition: In rats, giving progesterone and estrogen cyclically was better for cognition than estrogen alone, but this was not true when the treatment was given continuously. These studies lend more evidence to the idea that different progestins affect cognition differentially, but that well-timed administration can have a significant beneficial effect on cognition. It is important that research into the timing of the treatment continue, since many hormone therapies use a continuous regimen, which may not be the best choice when it comes to brain function.

CONCLUSION

Progestins are a crucial part of contraceptive and hormone therapies. Progestin-containing contraceptive drugs account for an increasing proportion of modern contraceptive formulations used by women around the world. In the United States, medroxyprogesterone is the most prescribed progestin and the progestin used in hormone therapy studies including the Women's Health Initiative and Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. Other countries often use other forms of the drug. Typically, progestins for clinical use are administered over many years to decades, depending on the treatment. For example, the Norplant implant delivers a constant dose of levonorgestrel for five to seven years.

Despite the widespread use of progestins around the globe, relatively little is known about the effect of long-term treatment in the brains of women during and following their reproductive years. Animal and human studies strongly suggest that progestins have important effects on neurological function, ranging from regeneration in the brain to cognition.

These effects may be both positive and negative, as progestins appear to protect the brain against certain forms of degeneration while making it more vulnerable to others. The range of neurological and cognitive effects progestins have on the brain make it especially important for researchers to continue to tease apart the circumstances under which progestins may be an advantage or a drawback to the brain, whether during the reproductive years or beyond.

If you have questions about the use of progestins, or are interesting in making changes to your treatment routine, it is important to talk to your doctor first. He or she can answer specific questions about the benefits and risks involved with hormone treatment.

Image: Ioannis Pantzi/Shutterstock.

This article originally appeared on TheDoctorWillSeeYouNow.com, an Atlantic partner site.